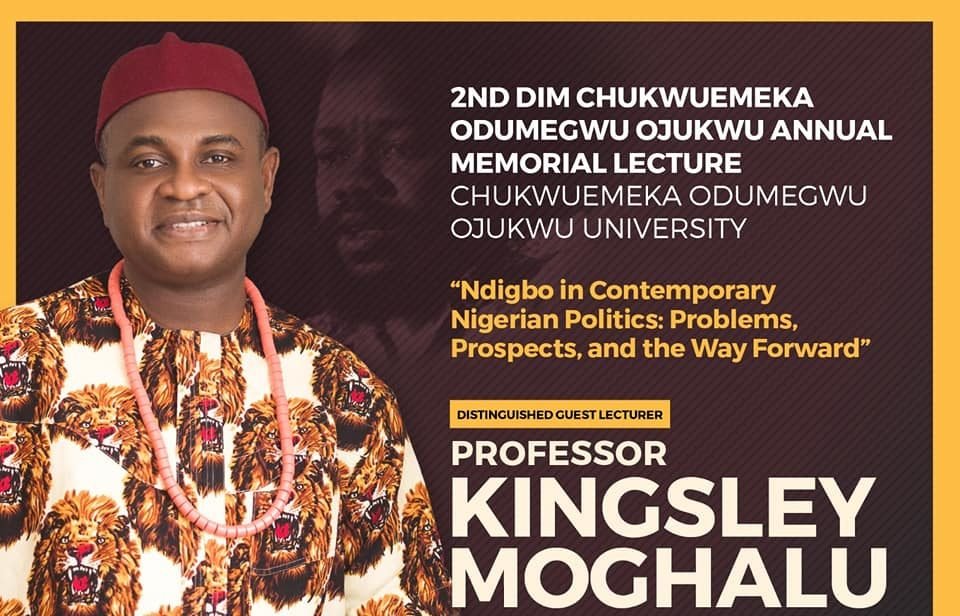

The 2nd Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu Annual Lecture Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University (Anambra State University), Igbariam Campus. November 4, 2019. By Professor Kingsley Chiedu Moghalu, PhD, OON, FCIB, LLD Former Deputy Governor, Central Bank of Nigeria Governor, Convener, To Build a Nation (TBAN) Protocols. I thank the Vice, Chancellor, Senate and Council of the Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University for the honor of inviting me to deliver the 2nd Chuwkuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu Memorial Lecture, a lecture series established in a fitting tribute to the legend after whom this great university is named. This is the second honor that this university is giving me. I recall that, in April 2017, at your 8th Convocation Ceremony, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University conferred on me the degree of Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) Honoris Causa. Thank you, Ojukwu University. Introduction: Ojukwu in Nigerian History Today is the posthumous birthday of the Late General (Dim) Emeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, Ikemba Nnewi, who passed on in 2011 at the age of 78. We celebrate a great man. Emeka was a great son of a great father, Sir Louis-Phillip Odumegwu Ojukwu who was the wealthiest Nigerian of his era in the 1940s, 50s and 60s. We celebrate a man who, though born into wealth and privilege, educated at Kings College, Lagos, Epsom College in Surrey, UK, and the University of Oxford where he obtained a M.A. in History, went on to chart his own independent path in life, and in the process attained greatness in his own right. We celebrate a legend, a visionary African of courage who took an indelible place in history with his leadership of Eastern Nigeria as Military Governor at a time of grave national crisis, and in the shortlived Republic of Biafra. Ojukwu the legend was the product of an historical accident that met a man of courage. Cometh the hour, cometh the man. He was thus a product of his times, just like all the major actors in the Nigerian civil war. We must therefore judge him in history strictly in that context, for without the large-scale massacres (pogrom) of Igbos in the Northern region of Nigeria after the July 1966 counter-coup (Crimes against Humanity under international humanitarian law), there would have been no Biafra. Without the controversial failure of the Aburi Accord in early 1967, there also likely would have been no Biafra. These two factual points are important because Nigeria continues to wrongly hold Ndigbo as a people collectively guilty of the secession attempt, as if Igbos woke up one bright morning and decided to leave Nigeria. As the Igbo proverb says, nwata na ebe akwa, onwere ihe na eti ya (a child does not cry without a reason). Clearly, then, those who blame Ojukwu for the effort by Igbos, under his leadership, to break away from Nigeria at that particular time and in the prevailing circumstances, are those who thrive in self-serving historical narratives. The reality of the time was that, owing to an unfortunate set of circumstances, the security of the lives and property of Igbos in Nigeria could no longer be guaranteed. Ojukwu simply answered the call of duty. He rose to the occasion as a result of the weight and burden of historical responsibility upon his soldiers. The real and relevant question, looking back now, is: could the war have ended earlier in a negotiated settlement rather than the military collapse of Biafra and the short-lived republic’s ultimate surrender? At any event, we must recognize that President Shehu Shagari’s noble decision to officially pardon Ojukwu — even if there were clear domestic political calculations embedded in it — and the former Biafran leader’s return to Nigeria in 1982, 12 years after the civil war ended, was one of the most remarkable attempts at nation building in Nigeria. While this lecture is in honor of Emeka Ojukwu, he is not the topic, however, but only a part of it. I have begun with this brief discourse on him because it is a lecture in his memory, and because his decisions and actions have had a strong impact on the place of Ndigbo in contemporary Nigerian politics. It is to that larger subject, therefore, that we must now turn. Ndigbo in Contemporary Nigerian Politics Who are the Igbo? History traces settlement in Igbo land back to 4500BC, but more recent history goes back to the founding of the Kingdom of Nri in the 10th century. The Nri Kingdom is credited with the foundation of the culture, customs and traditional religious practices of the Igbo, and is the oldest existing monarchy in Nigeria today. Igbo land officially became a British Colony in 1902 and part of the amalgamation of Nigeria in 1914. Occupying an area of 40,000 square kilometers, Igbo land has an estimated population of 40 million people (excluding its Diaspora), making the Igbo one of the largest single ethnic groups in Africa. The contemporary political history of the Igbo in Nigeria is marked by certain milestones, and is also defined by certain characteristics of both the Igbo and other ethnic nationalities in Nigeria. These events include: the massacres of Igbos in Jos in 1945 in which thousands of ethnic Igbo were killed by the Hausa, Fulani and Birom, with their property destroyed or looted. The next was the incident in 1951 in which the popular and the charismatic Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe (Zik), later to become Nigeria’s first ceremonial Governor-General and President after independence in 1960, and his party the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) lost the battle to form a government after the Western Region elections in 1951 (with Zik as the Premier of Western Nigeria) when politicians of the Ibadan Peoples Party cross-carpeted to support the Action Group to form a government with Chief Obafemi Awolowo as Premier. This loss ultimately forced Zik, whose party the NCNC previously dominated politics in both Eastern and Western Nigeria , to return to the Eastern Region in 1953 after a couple of frustrating years as Leader of the Opposition in