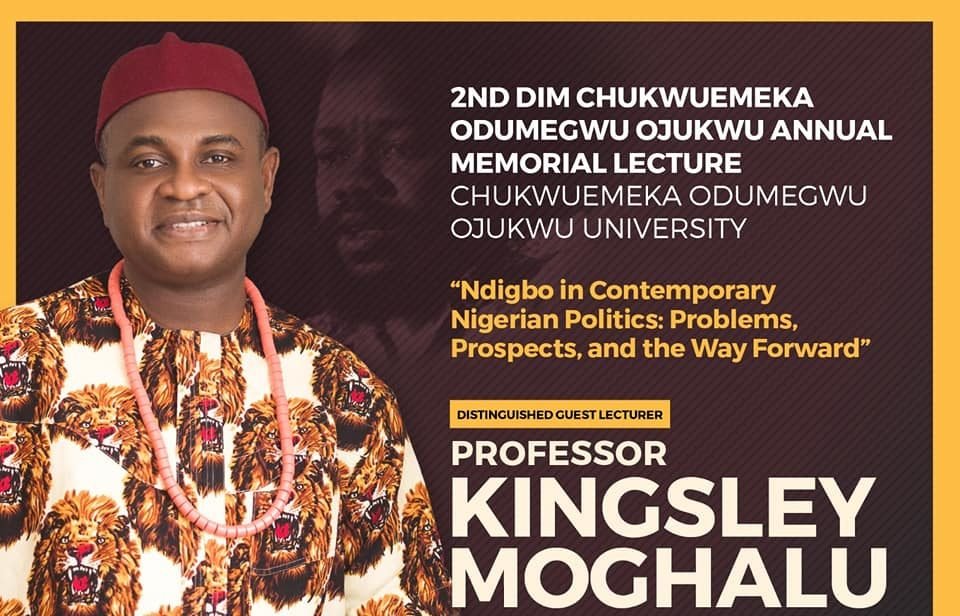

The 2nd Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu Annual Lecture

Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University (Anambra State University), Igbariam Campus.

November 4, 2019.

By

Professor Kingsley Chiedu Moghalu, PhD, OON, FCIB, LLD

Former Deputy Governor, Central Bank of Nigeria Governor,

Convener, To Build a Nation (TBAN)

Protocols.

I thank the Vice, Chancellor, Senate and Council of the Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University for the honor of inviting me to deliver the 2nd Chuwkuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu Memorial Lecture, a lecture series established in a fitting tribute to the legend after whom this great university is named. This is the second honor that this university is giving me. I recall that, in April 2017, at your 8th Convocation Ceremony, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University conferred on me the degree of Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) Honoris Causa. Thank you, Ojukwu University.

Introduction: Ojukwu in Nigerian History

Today is the posthumous birthday of the Late General (Dim) Emeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, Ikemba Nnewi, who passed on in 2011 at the age of 78. We celebrate a great man. Emeka was a great son of a great father, Sir Louis-Phillip Odumegwu Ojukwu who was the wealthiest Nigerian of his era in the 1940s, 50s and 60s. We celebrate a man who, though born into wealth and privilege, educated at Kings College, Lagos, Epsom College in Surrey, UK, and the University of Oxford where he obtained a M.A. in History, went on to chart his own independent path in life, and in the process attained greatness in his own right.

We celebrate a legend, a visionary African of courage who took an indelible place in history with his leadership of Eastern Nigeria as Military Governor at a time of grave national crisis, and in the shortlived Republic of Biafra. Ojukwu the legend was the product of an historical accident that met a man of courage. Cometh the hour, cometh the man. He was thus a product of his times, just like all the major actors in the Nigerian civil war. We must therefore judge him in history strictly in that context, for without the large-scale massacres (pogrom) of Igbos in the Northern region of Nigeria after the July 1966 counter-coup (Crimes against Humanity under international humanitarian law), there would have been no Biafra. Without the controversial failure of the Aburi Accord in early 1967, there also likely would have been no Biafra. These two factual points are important because Nigeria continues to wrongly hold Ndigbo as a people collectively guilty of the secession attempt, as if Igbos woke up one bright morning and decided to leave Nigeria. As the Igbo proverb says, nwata na ebe akwa, onwere ihe na eti ya (a child does not cry without a reason).

Clearly, then, those who blame Ojukwu for the effort by Igbos, under his leadership, to break away from Nigeria at that particular time and in the prevailing circumstances, are those who thrive in self-serving historical narratives. The reality of the time was that, owing to an unfortunate set of circumstances, the security of the lives and property of Igbos in Nigeria could no longer be guaranteed. Ojukwu simply answered the call of duty. He rose to the occasion as a result of the weight and burden of historical responsibility upon his soldiers. The real and relevant question, looking back now, is: could the war have ended earlier in a negotiated settlement rather than the military collapse of Biafra and the short-lived republic’s ultimate surrender? At any event, we must recognize that President Shehu Shagari’s noble decision to officially pardon Ojukwu — even if there were clear domestic political calculations embedded in it — and the former Biafran leader’s return to Nigeria in 1982, 12 years after the civil war ended, was one of the most remarkable attempts at nation building in Nigeria. While this lecture is in honor of Emeka Ojukwu, he is not the topic, however, but only a part of it. I have begun with this brief discourse on him because it is a lecture in his memory, and because his decisions and actions have had a strong impact on the place of Ndigbo in contemporary Nigerian politics. It is to that larger subject, therefore, that we must now turn.

Ndigbo in Contemporary Nigerian Politics

Who are the Igbo? History traces settlement in Igbo land back to 4500BC, but more recent history goes back to the founding of the Kingdom of Nri in the 10th century. The Nri Kingdom is credited with the foundation of the culture, customs and traditional religious practices of the Igbo, and is the oldest existing monarchy in Nigeria today. Igbo land officially became a British Colony in 1902 and part of the amalgamation of Nigeria in 1914. Occupying an area of 40,000 square kilometers, Igbo land has an estimated population of 40 million people (excluding its Diaspora), making the Igbo one of the largest single ethnic groups in Africa.

The contemporary political history of the Igbo in Nigeria is marked by certain milestones, and is also defined by certain characteristics of both the Igbo and other ethnic nationalities in Nigeria. These events include: the massacres of Igbos in Jos in 1945 in which thousands of ethnic Igbo were killed by the Hausa, Fulani and Birom, with their property destroyed or looted. The next was the incident in 1951 in which the popular and the charismatic Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe (Zik), later to become Nigeria’s first ceremonial Governor-General and President after independence in 1960, and his party the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) lost the battle to form a government after the Western Region elections in 1951 (with Zik as the Premier of Western Nigeria) when politicians of the Ibadan Peoples Party cross-carpeted to support the Action Group to form a government with Chief Obafemi Awolowo as Premier.

This loss ultimately forced Zik, whose party the NCNC previously dominated politics in both Eastern and Western Nigeria , to return to the Eastern Region in 1953 after a couple of frustrating years as Leader of the Opposition in the Western House of Assembly. This is widely believed, rightly or wrongly, to be the beginning of ethnicity as the basis of Nigerian politics. This watershed incident was followed by the massacres of Igbos in Kano in 1953 (ironically, it appears, as “soft targets” in an action targeted primarily at the Yoruba politician Ladoke Akintola of the Action Group party who, however, failed to turn up).

The other key historical markers were the January 1966 coup led by Major Kaduna Nzeogwu, tagged an “Igbo Coup” in the dominant historical narrative in Nigeria by non-Igbo ethnic groups, the July 1966 counter-coup (“Northern coup”), and the civil war of 1967- 1970 in which between two and three million of Igbos lost their lives. This was followed by the aftermath of the civil war in which, despite a declaration of a “No Victor, No Vanquished” policy by then Head of State Gen. Yakubu Gowon, Igbos were subjected to the discriminatory “20 Pounds” policy in which they were given only 20 pounds in Nigerian currency regardless of the value of the Biafran pounds in their possession, as well as the “Abandoned Property” crisis in which the properties of Igbo that they abandoned in other parts of Nigeria (especially today’s South – South region) were seized after they ran back to Igbo land in 1967 out of fear for their personal safety, were confiscated. In sum, the history of the Igbo in Nigerian politics has always been that of overreactions to perceptions of “Igbo domination” of Nigeria.

The narrative that the January 1966 coup was an “Igbo” coup has largely framed the Igbo in contemporary Nigerian politics, in particular the relations between the Igbo in the Southeast and Northern Nigeria. I believe the January 1966 coup was, looking back, a big mistake, but not because it was an “Igbo” coup, because from the historical accounts, it was not conceived as such. It was a strictly military affair, within the armed forces, and its planners and participants included several non-Igbo military personnel. There was no known, concerted group ethnic Igbo effort in its planning even inside the military, let alone outside the armed forces. Indeed, indications from some historians are that the main purpose of the coup was to release Chief Obafemi Awolowo from prison, where he was serving his sentence after conviction on treasonable felony, and install him as Prime Minister. A whole ethnic group cannot bear the responsibility for the actions of a few individual members of it, just as, for example, all Fulani in Nigeria today cannot bear responsibility for the criminal and terrorist acts of herdsmen who may happen to be Fulani.

In any case, the Nzeogwu coup was frustrated and defeated by military officers of Igbo origin such as Gen. Thomas Aguiyi-Ironsi and Col. Emeka Ojukwu, although the genie was already out the bottle. The lopsidedness of the execution of the Nzeogwu-led coup, in terms of high-level casualties, cannot also be glossed over. Understandably painful as it was, however, we have to tell ourselves the truth that the reactions to it, which continue to this day, have been extremely disproportionate. The January 1966 coup was a mistake (just as the July 29 coup was a second historical error, and two wrongs don’t make a right) because it was deeply naïve and was unnecessary. The civilian politicians of the time would ultimately have resolved the political crisis in the country if there had been no military intervention. If the frustration was about the corruption of the politicians of the time, well, Nzeogwu would turn in his grave if were alive today, and would doubtless have concluded that he made a big mistake, for the corruption then was a kindergarten class compared to what obtains in Nigeria today!

Here I must tell a personal story. On October 19, 2019 I put out a birthday message on social media to Gen. Dr. Yakubu Gowon, Nigeria’s former Head of State, a former leader with whom I admit to a personal friendship of many years, beginning during my career in the United Nations in the early 1990’s. Perhaps because of my use of the word “humane” in describing Gen. Gowon from my personal knowledge of him, I was heavily criticized by hundreds of Twitter users, mainly but not exclusively Igbo, who felt I was wrongly celebrating a leader they hold responsible for the deaths of millions of Igbo people during the civil war. There is no more appropriate place and occasion than this lecture to address the misconception that I was insensitive to the deaths of our family members, young and old during the terrible civil war. This was far from my intention because in my message I urged Gen. Gowon to step forward and play a leadership role in bringing the painful issue of the civil war and its lessons to closure so that Nigeria can heal. Because clearly, despite the no victor, no vanquished policy, Igbo people have remained heavily discriminated against in Nigeria in many ways, in particular in the political terrain in which there appears to be an unspoken conspiracy to prevent a person of Igbo ethnic nationality from becoming President of Nigeria.

In the words of the newspaper columnist Reuben Abati in a recent column on Gowon’s 85th birthday with the caption “Gowon at 85 and Fani-Kayode” (THISDAY, October 22, 2019) Dr. Abati wrote, inter alia “Let no one be in any doubt about it, the civil war, 1966 – 1970, will always be a big question at the heart of Nigerian politics and inter-ethnic relations. In many ways, there is indeed clear evidence that the war against Igbos has not ended. Nigeria nurses a huge, deep-seated prejudice against the Igbo man. It is the reason why there is no much dithering over whether an Igbo President should one day emerge or not…”

Let me return to my controversial tweet on Twitter. In the first place, I am deeply sorry, and apologize, to everyone whose sensitivity I offended if I mistakenly conveyed the impression that I as an Igbo man was uncaring about the millions of people, mostly Igbo, that perished in the war. Nothing could have been farther from the truth or my intentions. Consider my personal history:

First, it happens that I hail from Nnewi, Ojukwu’s hometown, and do plead guilty to some sentimental fraternal regard for the late Biafran leader. Second, if you are old enough and had the privilege of owning a Biafran passport, a symbol of Biafra’s success in attaining diplomatic recognition by several countries as a sovereign state for the period it existed, take a close look and you will see whose signature was on the Biafran passport and made it a valid document: Isaac Moghalu, my late father, a former Nigerian Foreign Service Officer who returned to the Cabinet Office of the Eastern Region Civil Service in early 1967, and later headed the consular services of the Biafran Ministry of Foreign Affairs after the region declared itself an independent republic.

Third, I lost my uncle, my father’s younger brother Godson Moghalu. He was a Biafran solder, killed in 1969 at the war-front. I still remember, like yesterday, my paternal grandmother’s anguished wailings at her son Godson’s funeral in our hometown of Nnewi.

Fourth, I remember our air raid bunker in our family compound in Nnewi during the civil war and the rush into its ambience –complete with seats carved from the earth – during air raids; I remember eating fried crickets and grasshoppers during the war.

The point is that, even as a child from age four to seven, I too lived the experience of Biafra. It was personal. It was harrowing.

But we need to heal, forgive collectively and move on as a country. Difficult as it might be, the Igbo should not remain permanently bitter about the loss of the lives of our loved ones. If we remain permanently bitter, we can’t heal. And if we can’t heal, we can’t compete effectively in the political terrain in Nigeria. But, realistically, the burden is far less on the Igbo who were the main victims of the tragedies of war but nevertheless have largely integrated back into Nigeria since the war, except, I would argue, in the political terrain, than it is on non-Igbo Nigerians who continue to resent the Igbo based on distorted historical narratives.

I believe that the class of today’s military generals who fought to keep Nigeria one, and who later emerged as military-political leaders, bears an even heavier burden of history to close this horrible chapter by putting it in its proper and more accurate perspective. Among this class, Gen. Gowon as Commander in Chief and Head of State during the civil war is uniquely placed to speak directly about the war, acknowledge the pain of the loss of millions of lives, and express regret for the loss of so many lives. It is a tragic failure of nation-building that Nigeria’s Federal Government sends official delegations to the annual commemoration of the Rwandan genocide, but refuses to confront and address our own history of conflict and the millions who died in its wake. And so, bitter memories fester. We have difficulty in moving on, because no one wants to address the pain directly.

Again, as an official of the United Nations who was involved in peace operations in Rwanda, Cambodia and Croatia in the early 1990s, I helped in my own humble way to bring peace, healing, and some degree of reconciliation in these countries with bloody histories that are making progress today. But they confronted their own history with war crimes trials and truth and reconciliation commissions. We have failed to do this in Nigeria. General Gowon declared after the civil war that “there will no Nuremberg trials in Nigeria”. That is just as well, for the question would have arisen: who will be prosecuted

– the defeated forces, in which case it would have been victors’ justice, or the victorious ones (for it is beyond dispute that war crimes were committed against Biafrans including the Asaba massacres), or both? I believe we owe ourselves, as Nigerians, closure. Our former military leaders who prosecuted the war need to show leadership in this matter. President Olusegun Obasanjo attempted an exercise in national reconciliation with the Oputa Panel. But, for a variety of reasons, the effort was not successful.

I also remember General Gowon’s visit to our family compound in Nnewi on December 30, 2005 for the inauguration of the Isaac Moghalu Foundation (IMOF) in memory of my father, an occasion at which he was the Chairman and Special Guest of Honour. It is notable that he made a conscious choice to participate in this event in Nnewi instead of a major meeting of Middle Belt stakeholders he was billed to address, and which clashed with our family event, but to which he delegated General Domkat Bali to represent him. I believe it was Gen. Gowon’s first visit to Nnewi town since the end of the civil war. Without prejudice to the larger issues of Nigerian history under discussion here, I will always appreciate the former Head of State’s decision to honor my late father and I in this manner. Several Nigerian dignitaries who happen to be Igbo, including the late Dr. Alex Ekwueme, former Vice-President of Nigeria, Chief Emeka Anyaoku, the former Secretary-General of the Commonwealth, Chief Arthur Mbanefo, former Nigerian Ambassador to the United Nations, Chief Chris Ngige, Governor of Anambra State, joined us for the occasion. I recall that the members of our local community in Nnewi warmly welcomed Gen Gowon in their midst. This was, in my view, a leader who wanted reconciliation.

But, Nigeria’s “Igbo problem” remains, and it has led to the revival of neo-Biafra movements, the most prominent of which is IPOB. Again, instead of addressing the root issues of the absence of equity and justice in our country, the near-complete alienation of the Igbo from a serious sense of co-ownership of the Nigerian project, our political authorities engage in convenient obfuscation and double standards. They celebrate a “unity” of Nigeria that clearly is a myth, but avoid addressing the National Question: Is this construct we call Nigeria a nation? If, so on what basis, and if not, why? They stress the indivisibility and “indissolubility” of Nigeria, but on whose terms? An indissoluble Nigeria in which some believe they are political masters and others believe they are being treated as political slaves and (rightly) reject that status? Our leaders have, again conveniently, labeled IPOB a “terrorist” group, but the real terrorists in Nigeria kill and maim with impurity and no accountability.

This is no way to build a Nation. We must all reconsider, and act differently to one another, if we want to remain one country. Let me be clear, my preference, as I believe is that of a great majority of the Igbo, is to remain part of Nigeria, and I do believe that, with a certain kind of national leadership, it is possible to build a Nigerian nation that can manage its diversity, and achieve stability and prosperity. But that outcome MUST be anchored on (a) justice, equity, and equality for all citizens of Nigeria, and (b) a fundamental constitutional restructuring of the Nigerian federation to return it to a real practice of federalism instead of the “unitary federalism” we have today. Outside of these two pre-conditions, Nigerians should sit across the table, look each other in the eye, and discuss what our peaceful options are.

The Igbo are hardworking, aggressive (sometimes loud!) professionally and commercially savvy, hospitable, adventurous, republican by nature, but politically weak, especially since the civil war. Ndigbo now appear to have been psychologically and politically defeated by the combination of the outcome of the civil war and the silent conspiracy to keep them from political power. So, we now have a “second fiddle” mentality, unable to assert ourselves politically as a cohesive force in a national polity which, sadly, remains driven by geopolitical and ethnic tendencies despite the wish and drive of some of us that it should graduate to issues-based and ideological politics.

While our politics as a country ought to move beyond ethnic considerations, all parts of Nigeria should embrace this approach at the same time. It must not be conveniently used as an argument to deny the Igbo an opportunity to produce a Nigerian President. When I ran for President in 2019, I did not run as an ethnic candidate. I ran on the basis of a clear vision for Nigeria, one in which our diversity would be managed well by consciously building a nation instead of a “it’s our turn to eat” approach (apologies to the author Michaela Wrong who wrote a book of that title), and ethnic “revenge” against perceived marginalization. I ran on a vision for the economic transformation and wealth creation for the citizens of Nigeria – North, East, West and South. Several individuals and voters told me they admired my vision and courage, but it was still the “turn” of the North. That of the Igbo, they said, would come in 2023. Nevertheless, I know that my 2019 candidacy, despite its appeal across ethnic boundaries, was seen by many as a “daring” novelty partly because I am Igbo. If that is the case, I have no apologies for indirectly making a statement that Nigeria belongs to us all, that I believed passionately that I had something to offer our country as a collective, and that I don’t see myself as politically inferior to any one simply on the grounds of ethnic identity.

Other characteristics of Ndigbo we must address include the reality that Igbo politicians in contemporary Nigerian politics have been largely self-seeking, and are unable to come together to advance their group interest within Nigeria. While this trait has been unfairly exaggerated as part of a convenient narrative, to the extent that other large ethnic groups in Nigeria also have internal divisions, it remains basically true. There are problems in the Southeast states of Nigeria that were caused not by any Hausa-Fulani or Yoruba Nigerian in Abuja, but rather by the leadership failures of Igbo politicians in leadership positions in these states, and can be addressed without waiting for Abuja to give us solutions. These include environmental and urban planning disasters in places like Aba and Onitsha. The latter is, in addition to having the largest single market in Africa, the most polluted city on earth, according the World Health Organization. Other challenges include the failure to advance an effective agenda for Nigerian youth in the Southeast that can create jobs, and the failure to develop a robust Southeast regional economic development zone such as the Development Agenda for Western Nigeria (DAWN) initiative. Moreover, many Igbo businessmen have also been largely self-seeking. They fail to see how they can invest for certain political outcomes and instead focus exclusively on their individual business interests.

The Path Forward

The truth is that the Igbo remain divided today between the pan-Nigerian vision of the Great Zik and the more “realistic” one of Ojukwu that paralleled the political dispositions of Chief Obafemi Awolowo in the Southwest and Ahmadu Bello, the Sardauna of Sokoto, in the core North of Nigeria. I believe it is possible to bridge the two, but Ndigbo cannot do it alone if other major ethnic nationalities in Nigeria continue with business as usual.

So here are my recommendations:

First, to address Nigeria’s challenge of nation-building today, the Nigerian civil war and its impact should no longer be swept under the carpet by both our present leadership at national and state levels, as well as the leading actors of the war who are still alive today. Our national attitude to history must change. History is a tool for healing and nation-building. This is the approach taken in all developed countries with challenging histories such as Germany, Japan, South Korea, and the United States. The war must be addressed with recognition of the millions who died, and a simple and straightforward “I am sorry that this happened; I feel the pain of it all. Let us forgive” from the leading actors of the conflict.

Second, Ndigbo should pursue the agenda of BOTH constitutional restructuring and the election of a competent, visionary Nigerian from the Southeast geopolitical zone as President of Nigeria in 2023 as a matter of priority, persuading, lobbying other parts of the country within the democratic context of the imperative of this approach in order to rebalance Nigeria along the lines of equity and justice. Ndigbo have approximately 30 million voters of Igbo ethnic nationality in the Southeast, the Northern states, and the Southwest. It is time for these votes to be organized and channeled in a more strategic manner.

What people wrongly describe as the “Igbo presidency” rather than a Nigerian president of Igbo origin, and constitutional restructuring, are not mutually exclusive(Barack Obama did not run a “Black American presidency” because he was the first black President of the United States, it was still an American presidency.) Both will be beneficial for all of Nigeria. I therefore beg to disagree with the view that Ndigbo should focus only on a campaign for restructuring and should be uninterested in the quest for the presidency. That is a defeatist approach, an implicit acceptance of a negative condition instead of a proactive struggle within a democratic context to overcome it.

Third, Ndigbo must take greater interest in the need for fundamental electoral reform. Arguing for restructuring while neglecting the imperative of electoral reform is short-sighted, for it is only an open and transparent electoral system, one with a truly independent electoral arbiter, that can throw up a leader who will lead the restructuring of Nigeria. Clearly, the leadership in Nigeria today lacks the will to take this essential step to make Nigeria work again.

Fourth, Ndigbo must redouble efforts at regional integration and infrastructure in the Southeast states. Success in this quest will benefit the region and even Nigeria as a whole.

Fifth, Ndigbo should aggressively pursue the renaissance of Igbo culture and language at home and abroad in order to restore Igbo self-confidence. I am very pleased to see that this is already happening. The origins of Nollywood are mainly Igbo and, after lagging behind Yoruba and Hausa TV entertainment channels, Igbo artistes now have one. There are now “Igbo Days” on Twitter when Ndigbo tweet completely in Igbo language – and other Nigerians from other ethnic groups have asked for translations in English so they too can join the fun! There must be a unified Nigerian world view if our country is to prosper. But there also can be an Igbo worldview within the Nigerian one, a worldview that is not anti-Nigerian but promotes Igbo culture and cosmology while reaching out across ethnic divides.

Sixth, special effort must be put into achieving an Igbo-Yoruba entente that breaks the mistrust of the past between the two main ethnic blocs, just as engagement with our brothers in the North remains essential. This should be a positive, not negative, use of inter-ethnic relations. I am pleased to see a far greater intermingling of our young people across ethnic boundaries, and, in particular, it appears that young Igbo and Yoruba are marrying themselves as if the world will end tomorrow!

Conclusion

Ndigbo need to undertake a thorough self-appraisal of their place in contemporary Nigerian politics along the lines I have indicated above. We must become more confident in Nigerian politics. As Socrates famously said, the unexamined life is not worth living. Nigeria, on the other hand, should stop asking the Igbo to prove their Nigerianness. Fifty years post-war, Ndigbo do not need to prove their commitment to Nigeria because that commitment is self-evident even to the blind. Ndigbo are, arguably, the most Nigerian of all the country’s ethnic groups. Our fellow country men and women should not, either willfully or innocently, confuse the picture of Ndigbo in Nigeria with the IPOB phenomenon.

IPOB is essentially a cry for justice, and there can be no peace in Nigeria without justice. The moment of truth is approaching in 2023. Another rejection of the idea of a Nigerian president from the Southeast will undoubtedly lead to greater ethnic radicalization and more widespread separatist tendencies in the region, with the likelihood that that tendency will finally go into the mainstream. This would be a dangerous development, and all who are genuinely committed to Nigeria’s unity should be concerned about this scenario in a preventive manner. It is time for the civil war to really end. Ndigbo deserve their place in the Nigerian sun, as of right as Nigerians and not at sufferance.

I conclude with a profound statement by Dr. Henry Kissinger, the former Harvard University professor who later became National Security Adviser and then Secretary of State of the United States. Commenting succinctly on the European Congress of Vienna’s magnanimous disposition to France after the Napoleonic wars, Kissinger wrote: “It is the temptation of war to punish, the task of policy to construct. Power may sit in judgement, but statesmen must look to the future”.

Thank you. God bless Ndigbo. God bless Nigeria.